In the business world, and especially on projects involving technology or disruptive transformation, the best path forward is often unknown. You’ll encounter many situations where choices will need to be made without enough information.

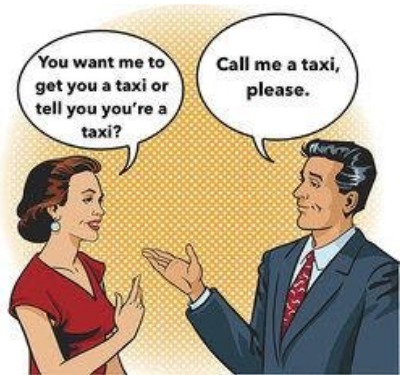

You’ll also encounter team members who are…let’s say fuzzy in their communications, which can, if you’re not careful, lead to major issues on a project.

Learning how to effectively handle ambiguity can improve how open you can be to people and various styles of communication, how quickly and intelligently you can make decisions in the absence of complete information, and how successful you can be in your leadership role on a project.

Let’s look at two types of ambiguity to contextualize when each occurs and how understanding the differences enables effective situational management.

Unintentional Ambiguity: Seeing the Same Thing Differently

When someone is unclear or imprecise (though not deliberately) and it leads to a misunderstanding, you have unintentional ambiguity. There are two problems that typically arise from this form.

The person giving the information incorrectly judges the recipient negatively. Sally tells Jimmy that his task needs to be done next week, though she doesn’t specify the exact deadline. When Jimmy doesn’t turn his project in on Tuesday (which is the deadline she had in her head), Sally thinks Jimmy didn’t listen to her, didn’t follow her directions, or isn’t up to the job. Given that Sally didn’t say the task was due Tuesday, Jimmy is actually not at fault, but that’s not Sally’s perception.

Conversely, the recipient of the information can misinterpret a statement or situation and judge the sender negatively. Jimmy is annoyed that Sally was so vague about the deadline and now he’s scrambling to get his work done. He’s left with a negative view about working with Sally. In the future, he won’t take her seriously when she makes requests.

You can see how both examples can lead to unintentional discord among team members. While this is the most easily avoided problem, as all it requires is clarification by either the sender or the recipient, it is also the most frequent type of ambiguity problem due to the nature of busy people operating from different assumptions.

Strategic Ambiguity: Gaining an Advantage Over Others

It is often assumed when someone is unclear or imprecise that it is unintentional or unconscious, that if Sally had known better, she wouldn’t have given such unclear direction.

This isn’t always the case. Some people intentionally inject ambiguity into a situation.

Strategic ambiguity, otherwise known as deliberate ambiguity, happens when someone intentionally distorts someone’s perception with the purpose of achieving a specific outcome. She skillfully and consciously is vague and indirect to gain an advantage.

Why? Here are a few reasons.

Sally wants to control the narrative. She may know the answer or outcome but revealing it will put her in a bad light. For example, if Sally tells Jimmy the task is due Tuesday, he might ask why, and she might have to tell him that she’s behind on her own tasks and needs him to finish his work early so she doesn’t look bad.

Sally might be leveraging the information for negotiation purposes. Revealing her position of being behind would put Sally at a power disadvantage, and perhaps they’ve both vying for the same promotion.

Sally might not want to commit. Being vague about the deadline allows her the time and space to make a decision when she feels comfortable or gives her time to find alternative options.

On the other side, Jimmy may choose to not clarify when he could do so for similar deliberate ambiguity reasons:

Jimmy wants flexibility. Not having a specific date gives him the excuse to complete it at a time of his choosing, with the ability to explain his choice of delivery due to Sally’s lack of a specific due date if he’s late.

Jimmy wants the request to go away. Not everyone follows through on their requests. Jimmy considers there’s a likely chance this request will be forgotten and if he goes along with the vague timetable, he can ignore it altogether.

Jimmy wants control. While he knows why the task is needed by Tuesday, Jimmy wants to use the opportunity of ambiguity left by Sally to make the production of the task at the last minute a favor or otherwise something that makes him look good despite Sally’s lack of clarity.

While this set of examples is not exhaustive, it helps to illustrate the basic elements of why rational, intelligent, and capable people can feign ignorance or otherwise create ambiguity.

Situations Where Ambiguity Arises on Projects and Approaches to Handle Them

Roles and responsibilities are the most common problem areas where ambiguity often occurs. If accountability and responsibility are not clearly defined, it creates room for political or opportunistic maneuvering if individuals have their backs against the wall. That’s why it’s important to clearly define who owns which deliverables, where one person’s responsibilities end and another’s begins.

Disincentivize gamesmanship! To make sure you have your bases covered, step through boundary conditions where roles overlap or where responsibilities are blurry. While you cannot think of every scenario, by going through the exercise you allow people to take ownership of their areas through examples and reinforce the behavior that in the face of ambiguity they should work to solve it rather than allow it to be someone else’s problem and allow the work to fall between responsibility gaps.

The second most common issue is when a stakeholder can’t make a clear concise description of the problem statement that needs to be addressed. Maybe they just want software integrations to “work better together.” That’s vague. What would that look like? Perhaps they don’t know and are afraid to admit that.

Ask probing questions to delve deeper and get specifics against which you can define the accurate problem statement.

“Which steps of the integration don’t work today?”

“What would it look like if it worked the way you wanted to?”

And so on. The breaking down of ambiguous problems into elements is often the best remedy as it helps everyone go through the process of stating their requirement without losing face for not really knowing how to say what they want. In this situation, as the recipient of the requirement, deliberately feigning ignorance also helps to get to the right outcome because it forces the requirement to be restated in several different ways to ensure that the original request was actually what was needed.

Use of this type of “feigned ignorance” to get to the truth of the need is the opposite of deliberate ambiguity by the recipient to simply take advantage of the ambiguous statement to produce something easily accomplished but incomplete and blaming the ambiguity of the requirement for the gap.

The third watch out is ambiguity in expectations. This one has many flavors, from what type of effort or work is expected as an outcome, to what “good,” “ready,” or “done” will look like, and everything in between.

The common factor to this type of ambiguity is everyone agrees on the “what” and the “when,” but it is the “how” something is supposed to be, look, or, act, that is the source of misunderstanding. The easiest way to spot this type of ambiguity is to watch and listen for specific examples of “how” something should be, and if there aren’t any being provided or different stakeholders are using different ones, that is a sure sign you have ambiguity of expectations. While there is no silver bullet for this type of ambiguity, a reliable best practice is to always ask for examples of what is expected, how something should act/look/work, how something would be considered as ‘failed’, or how the next step in the process would occur.

Understand Your Comfort Level with Ambiguity

Even armed with the toolkit to spot and address ambiguity problems, a large part of successfully managing ambiguity is understanding yourself. If you have a low tolerance for ambiguity, you probably have a high need for closure. Need for closure means you have a need for an answer on a given statement, problem, or situation. Sometimes you’ll take any answer!

What does this mean? On a good day, you move faster. On a bad day, you are more likely to make incorrect judgments and premature decisions. Forcing ‘clarity’ can make you feel like you have structure and a plan that you can act on, that others may reward you for acting quickly, or doing so consumes less mental effort and anguish.

But the problem with this approach without further nuance is the potential cost of prematurely making judgments and acting on them: making incorrect snap decisions that lead to costly errors.

The takeaway here is knowing your comfort level helps you understand how you perceive ambiguous situations and tend to respond to them. The more you can anticipate your reaction, the better you will be able to handle ambiguity when it comes your way.

Not sure how you handle ambiguity? Check out the Need for Closure Scale by Webster and Kruglanski to find out how much certainty you need in your life.

How to Manage Ambiguity: Turn Chaos into Order

There’s no getting around ambiguity on a project, so the key is in how you handle it. Ultimately you need to be able to walk into chaos and turn it into order. Here are a few good habits to keep in mind if you’re faced with a project that lacks clarity:

- Work with the client to understand their goals and objectives, asking for multiple restatements to ensure alignment.

- Listen to the client to understand their needs and wants. Use negative hypotheticals to triangulate what good looks like by contrasting it with what bad looks like.

- Don’t be afraid to ask questions, but don’t freeze if you aren’t able to get your questions answered. Timing is everything, and some questions require additional loops.

- Identify the critical path and agree up front when you have to move forward or when you need to persuade your team to move forward instead of waiting for more information.

- Mitigate expectations ambiguity: develop a project plan with agreed-upon criteria for success. This helps identify goals, reduce risk, ensure you meet deadlines, and meet or exceed the client’s expectations.

The fact in business and life is that you can control no one but yourself. Even if you can’t control whether others are vague or not, you can manage how you respond. Ask clarifying questions. Lead by example and be precise in your communications. Make allowances for differences that come with working with others, especially those with other life experiences and cultural backgrounds.

Ambiguity, if unchecked, can be a project-killer and can create discord among team members. Simply being aware of its presence and having a plan for cutting through the fog is a great first step to mitigating it. From there, create a culture that encourages employees to be precisely communicative, to leave a breadcrumb trail that others can follow, and to be impeccable with their words.